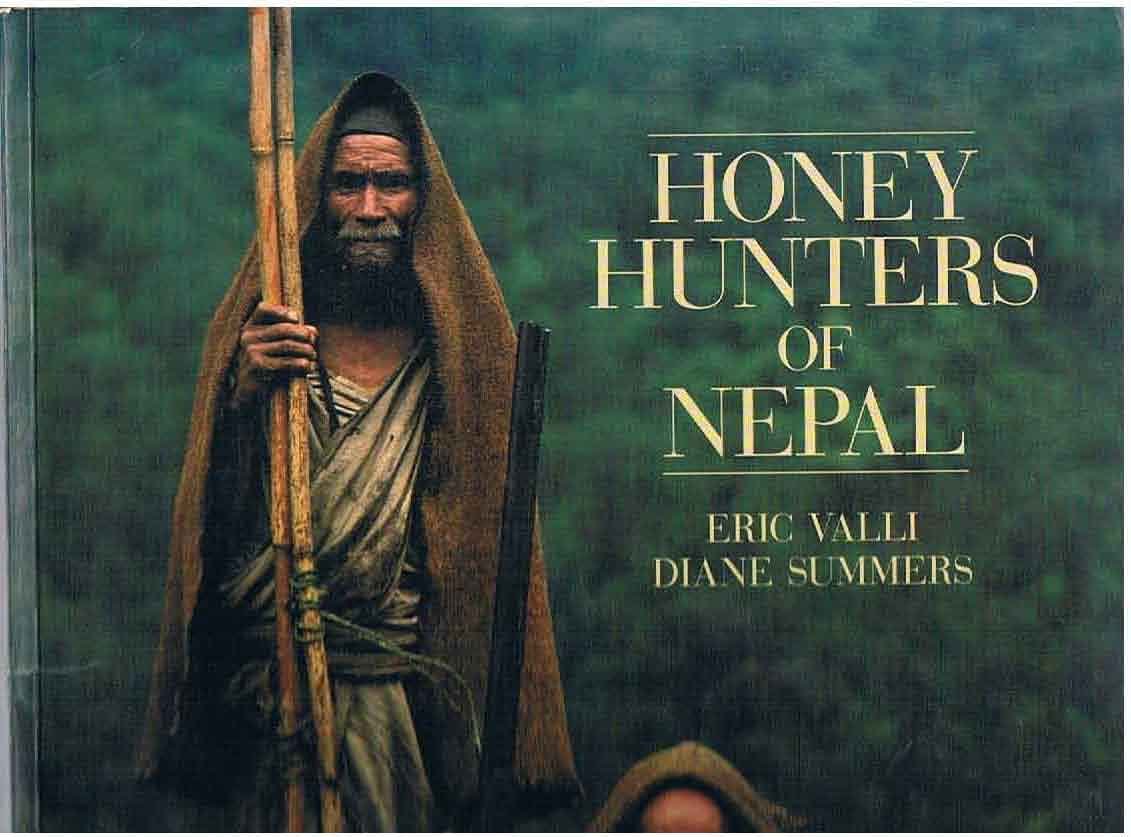

For the Gurung and Magar tribesmen of Central Nepal, honey hunting is much more than just an occupation; it is a lifestyle. The survival of entire clans of tribesmen depends on the honey hunters who practice the hunting of honey combs for making livelihoods possible in these regions of the mountainous nation. The tradition of honey-hunting has been carried on for centuries by these tribes and the skills required to procure these golden honey combs are unique to the hunters.

Along the foothills of the Himalayan cliffs lies a magnificent treasure of pure honey produced by thousands of Apis Laboriosa, which are the largest honey bees in the world. The bee nests are hidden in the south-west facing hollows of the cliffs for making them inaccessible to predators and more exposed to sunlight. The building of these honey-laden nests by the bees in such steep locations makes the task of honey-hunting not just daunting but life-threatening in nature.

The ancient practice of extracting honey from these steep foothills has not been modified for centuries as the essence of honey hunting in these regions rests in the fact that the task has to be carried out in a manner that does not disturb the natural habitat of this rare and decreasing population of bees.

The honey hunting usually takes place in the season of autumn and is a three day procedure, which follows a ceremony held by the villagers to please the cliff-gods and ensure the safe and successful return of the hunters from the hills. During the ceremony, a sacrifice of sheep and offers of flowers, fruits and rice are made to placate the gods. The men leave the tribes in groups for honey-hunting after the ceremony to collect honey from mountain cliffs which are usually a three to four hour walk from the villages.

A handmade rope ladder and long sticks called tangos, are all that the hunters rely on to complete this task of collecting honey combs. A hunter, called a ‘kuiche’ by the tribes people, clings onto the rope ladder while a smoke is made to rise into the steep hollows where the nests are placed. The smoke forces the bees to leave their nests and it is in this short period of time that the hunter must fill a hanging basket with honey combs using the sticks before they are lowered by other men in the team. While the honey is collected by one hunter at a time, a dozen other men support the hunter in carrying the hunt out, which is a must to ensure the safety of the hunter dangling by a rope some 200 feet above the ground.

The honey hunted is carried back to the villages and distributed among the villagers. The most basic use of the honey is to brew honey tea, fitting for the cold climate of these regions. Some of it is consumed while most of it is sold to outsiders. In recent days, the price as well as the demand of these natural honey combs is increasing rapidly. The medicinal value of the spring red honey has been recognized and countries such as Japan, China and Korea have become the main importers of this Himalayan honey for use in traditional medicines.

The concept of honey-hunting in Nepal as an adventure sport is gaining popularity among western tourists and accordingly, travel and tours companies have started offering honey-hunting as an adventure sport package. The tourists are accompanied by a honey-hunting team to watch the staged extraction of honey from the hills in the Annapurna circuit. Areas of Lamjung, Ghandruk and Manang are famous for these events. The tourists are charged upwards of $2000 dollars for the adventure and a very small percent of the sum is paid to the tribesmen. The attention that the art of honey hunting has gathered from tourists cannot be considered the best as it lures the honey-hunters to hunt out of season for additional money. Hunting off-season can risk lives of the hunters and destroy the bee-nests contributing to decrease in bee population and honey production.

Apart from this, the government has gained authority of these hills and is trying to hand it over to harvesting contractors for commercialization purposes. This will most likely leave the real honey-hunters jobless. The changing climate is also not helping the cause by delaying the hunting seasons from its normal period. The shifting of younger generations to the city is a major concern for the aging hunters, who have lived their entire lives in the hope of handing the tradition over to the next generation. A combination of these concerns put forward a greater concern: how much longer can this ancient tradition of honey-hunting be preserved in Nepal?

Let us know your thoughts regarding the issue in the comments below.